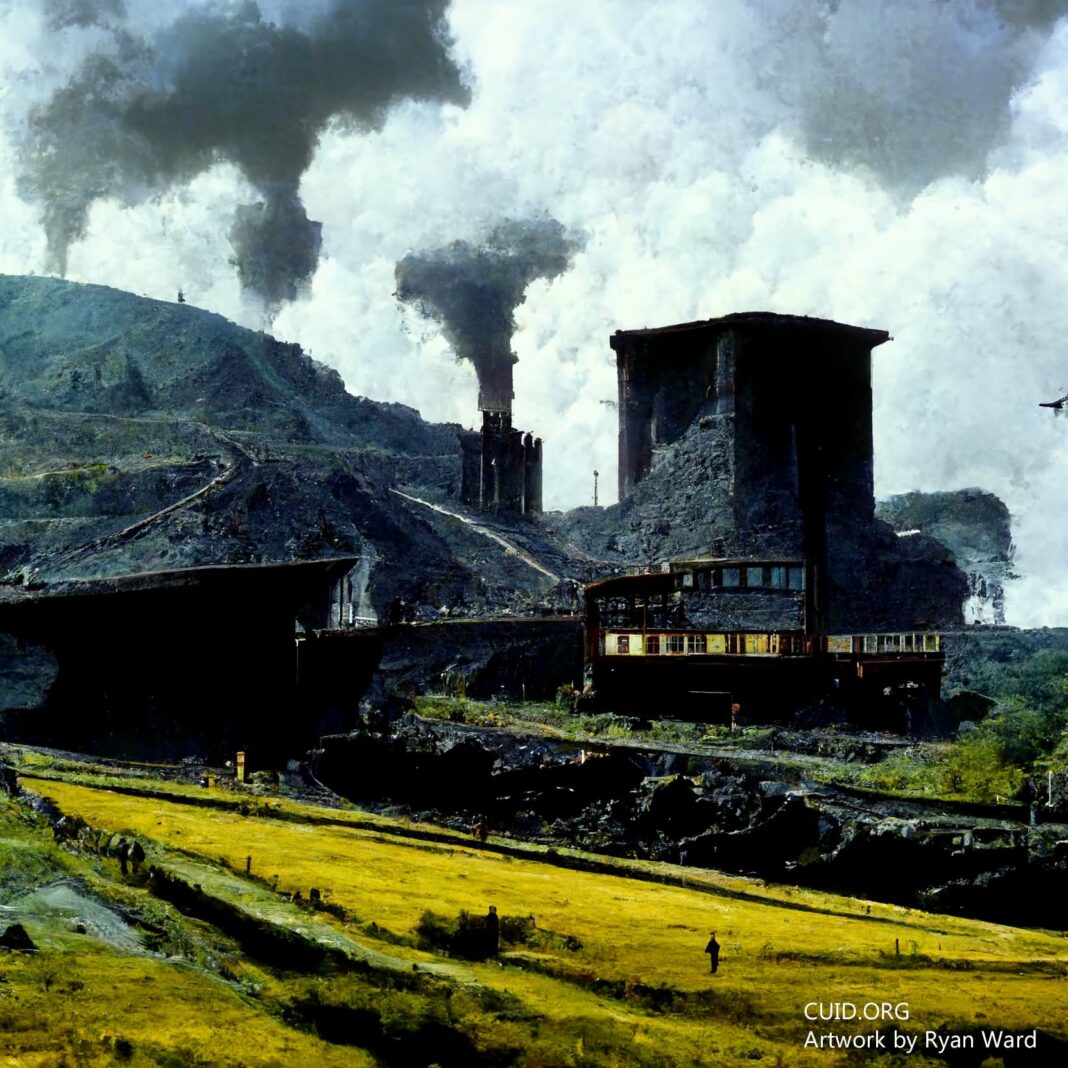

Published: Luke Thomas and artwork by Ryan Ward

In the 1960s, as theories surrounding climate change began to emerge, its consequences were already evident across the Welsh Valleys. At 09:13 on the 21st of October 1966 in Aberfan, 150,000 tonnes of coal waste buried a school. 144 people were killed; 116 of which were children. The events of that morning wiped out a generation of people from Aberfan. It was the last day of term and the school was closing early at noon – had the landslide occurred only a few hours later, it would have been empty. An estimated 6000 people have been killed in Wales as a result of coal mining; for them, the climate crisis began long before now, it began in the coal mines.

Coal has been at the very heart of the Welsh economy for centuries. It brought employment, opportunities and infrastructure. By the early 20th century, one in four workers in Wales were coal miners. The country was renowned worldwide for its slate and was home to one of the world’s largest coalfields. The desire for coal fuelled development across Wales; it became home to the world’s highest railway viaduct, the world’s tallest canal aqueduct as well as the first ever steam train. Railways were built to connect communities to the mines, which in turn allowed communities with one each other. Wales was even home to the first operational public railway in the UK, which ran from the Gwendraeth valley into my hometown of Llanelli. But, climate change tortured the Welsh economy. A desire for cleaner energy meant that fuel sources switched from coal to gas and biomass; and as the coal mines closed, so did the quarries, ports, and most importantly, the railways. When the coal mines and railways closed, communities became economically and socially isolated. The transport links were only built to exploit Welsh natural resources and not to connect the country; we’re yet to see a railway or a highway connecting the North and South.

Before the mining crisis, Wales’ economy kept up with the rest of the UKs, but the closure of the mines resulted in the Welsh GVA (Gross Value Added) falling to just 77% of the UK average by 1999. Some state that the decline of the Welsh economy is a clear example of Westminster’s mismanagement, not only of the 1980s mining crisis, but also of Wales. Today, Wales is home to the highest level of child poverty in the UK and is the only place to see child poverty levels rising. In my home ward, 41.3% of children live in poverty. Wales continues to suffer socio-economic issues three decades after the mining crisis and there is a clear need to reassess the policies surrounding the economic progression of the country. In contrast, London is the richest region in northern Europe, but Wales is the poorest. Adam Price, the leader of the nationalist party in Wales, stated that ‘the solutions to our problems will never come from another country’s capital 150 miles to the East.’ The devolution settlement, however, has meant that Wales now has a significantly greater say in its own affairs. The Senedd (Welsh Parliament), is responsible for many decisions including the Welsh NHS, education and the environment. The environment is one of the factors high on the national agenda and in October 2011, Wales was the first country in the UK to introduce a charge for plastic bags. More importantly, in April of this year, the Senedd was the first national Parliament in the world to declare a climate emergency.

A month after declaring the climate emergency, the Welsh Government controversially axed a scheme to build a £1.6bn M4 relief road. The relief road was to be built due to congestion around a two-lane tunnel which results in a bottleneck on the motorway. This was deemed a huge win for environmentalists, since the relief road would have ‘ploughed through the unique, wildlife-rich Gwent Levels, pumped more climate-wrecking emissions into our atmosphere, and ultimately caused even more congestion and air pollution’. Nonetheless, others claim that this decision could be detrimental to the much-needed investment along the south coast, in particular the Valleys which saw the blunt of the economic hardship after the mining crisis. Nonetheless, the First Minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, had the final say in the decision and stressed his concern about the surrounding wildlife and environment and that the project ‘would have an unacceptable impact on our other priorities such as public transport’. After the climate emergency was announced in Wales, the Welsh Government and Cardiff City Council both announced that they were to heavily invest in public transport. £58m is to be invested in Cardiff Central railway station and £119m has been secured from the EU to develop a South Wales Metro. The city council has also announced a £1bn scheme to transform public transport across the city to reduce car journeys. This scheme is to integrate with the South Wales Metro and is to include green and electric buses. A new bus station is set to open in Cardiff by 2023 and the scheme is expected to be complete by 2030.

Despite Wales suffering economic hardship from its over-reliance on mining of fossil fuels, climate change is no longer hindering development in Wales, but is in fact actively encouraging it. Wales currently outdoes the whole of the UK in terms of its renewable energy consumption, where it currently meets 48% of its energy demands by renewable sources compared to just 11% across the whole of the UK. It is also on target to reach 70% by 2030 and an ‘ambitious’ target from the Institute of Welsh Affairs predicts that 20,150 jobs could be created if Wales meets 100% of its energy needs from renewable sources by 2035. Climate change and investment in renewable energy could give the Welsh economy its much-needed boost. Currently, Wales is the fifth largest electricity exporter in the world, just behind Canada, Germany, Paraguay and France, whereas the British state is not even in the top ten. Wales produces enough extra electricity to almost satisfy the energy consumption of the whole of Scotland, but despite this, Wales pays more for its electricity than the rest of the UK, where the Welsh average is 15.13 p/kWh compared to the UK average of 14.40 p/kWh. Regulation of energy prices is not a devolved issue and as such the Welsh Government has no control over the effect of price hikes and austerity measures on the poorest region of the UK; meaning that several families in Wales have to choose between heating and eating.

Climate change is not only developing the physical landscape, but also the political landscape of Wales. In 2014, the UK Government announced a £1.3bn Swansea bay tidal lagoon, which could have brought over 2000 jobs and powered 155,000 homes. Labour, the Lib Dems, Plaid Cymru and even the Welsh Conservatives all supported the project, but in June 2018 the UK Conservative government scrapped it. On the very same day they voted for the £14bn expansion of Heathrow airport. As Wales was refused investment in green energy production, Westminster greenlit the expansion of the UKs biggest single source of greenhouse gases. This was not only a kick in the teeth to environmentalists, but also to those in Wales, as the promise of jobs and investment was broken. Further to this, the UK Conservative government also broke other environmental development promises including electrification of the South Wales railway lines past Cardiff, electrification of the North Wales railway lines and they failed to reach a deal for a nuclear power plant which would have brought 9000 jobs to Anglesey. Several political parties are calling for more devolved powers to allow for a greater degree of environmental control and energy production to give the green light to those projects rejected by Westminster. Some argue that this, and the economic hardship that Wales continues to endure proves that Westminster has not been making the correct decisions for them.

Whilst the worst of climate change is yet to come, Wales has already seen the human and environmental cost of fossil fuels over several centuries. Despite providing coal to the rest of the UK and the world for centuries, ironically a third of Welsh people now live in fuel poverty. But what goes around comes around, and as a result of climate change, there is a push for investment in public transport and renewable energy, driving economic development across Wales. Climate change may have resulted in the decline of the Welsh economy – but it could prove responsible for its revival too.